Photograph by Baudouin Mouanda

I was invited to speak at the Art Institute of Chicago on September 6, presenting a longer version of the paper I gave in the spring as part of the graduate student seminar (an annual gathering of art history students from midwestern universities; I represented IU). It was a treat! The Art Institute people were lovely, with special thanks to Annie Morse in Education.

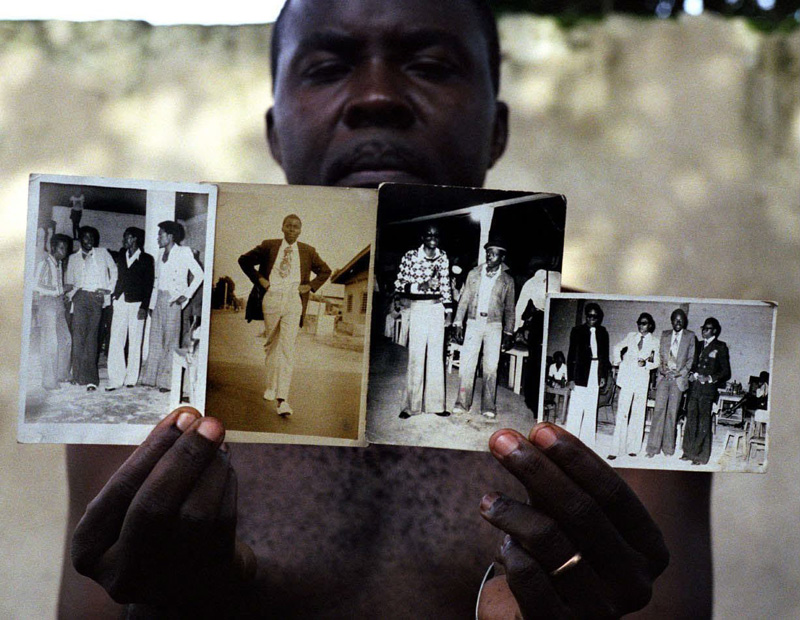

The lecture presented parts of a project I began in 2012 (it became my MA thesis) about photography and sapeurs, “The Pursuit of Elegance: Congolese Self-fashioning in Image and Action.” Sapeurs are fashionable central African (mostly) men who dress competitively in outrageous yet impeccable suits, seeking out griffes (labels/brands), dreaming of travel, and asserting their places in public space through performative fashion. There are different ways of understanding the sapeur movement: as imaginative escape from the grinding struggle of African urban life; as mimicry of Western modernity, either deluded (the colonial complex) or subversive; as a kind of narcissistic, or cynical, religion of consumption.

A 19th-century stone funerarysculpture by a BaKongo artist in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts

In the talk I was interested in making a couple of particular points that related the performances of sapeurs to other works of art, contemporary photographs and tradition-based sculptures. My understanding of sapeurs and other ambiguous fashion subcultures rests on certain fundamental assumptions. First, I view dress/clothing/the dressed body not as the expression of an already-existing ‘self’ but as the material that constitutes one’s self–your identity exists in practice, in process, constantly shaped by experience and action. Second, acculturation and cross-cultural borrowing are the norm, not the exception, in arts and fashions, but the paths and meanings of borrowed forms are not stable or predictable. Third, the body is both a self-creation and the site of socialization (consider how many rites of passage have special kinds of clothes to go with them, or witness how dress is often morally charged). As an art historian I am always interested in the agency of creative people, and stylish people dress as an action within or against a social milieu.

I used BaKongo sculptures to trace an aesthetic thread between older BaKongo ways of expressing and sustaining power, beauty, and personal status, and the modern language of la sape. In this way la sape can be seen as a kind of continuation of BaKongo values, theories of self and society, with and through aesthetic practices (albeit ones that invert or renegotiate the ‘real’ social order).

Photograph by Hector Mediavilla

I also discussed the performative nature of la sape–you must have an audience to be fashionable–in relation to photography, from early colonial portraits to mid-century family archives to dynamic contemporary art photography, and how the techniques and material qualities of photography suit sapeurs’ practice particularly well. Sapeurs go out into public places to show off their goods and the unique combinations of their outfits, to do battle in dance-like exhibitions of their labels and fine details. And sapeurs appreciate photography’s enhancement and extension of their fleeting performances through time and distance. Drawing on theories of performance, photography, and signs, I argued that the ambiguity of authorship in portraiture and sape photography is paralleled in sapeur’s strategic appropriation of cosmopolitan style.