I presented a paper in a panel themed around the notion of the “clandestine,” a fascinating frame. The paper grew from a project from a comp lit seminar with Akin Adesokan on African cosmopolitanisms in the 20th century. In the project I thought through ways that intellectual and political struggles around nation, modernity, and liberation can be worked on–and changed in unpredictable ways–at the site of the body, through techniques of consumption, performance, prohibition, and secrecy.

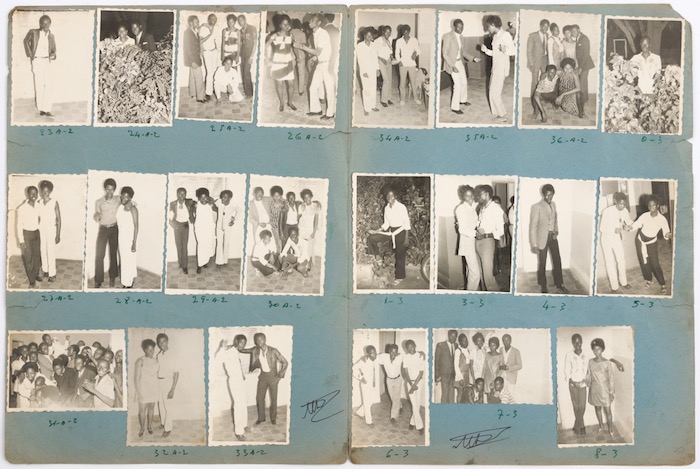

Malick Sidibe studio, Arrosage Kassim Dembele, 1970. Gelatin silver prints mounted on construction paper folder.

My subject was both a fashionable practice and its documentation, which are seemingly opposed. Several Malian friends have told me about how young people snuck out of the house wearing internationally-fashionable clothes hidden under local styles of wrapper or gown. This was meant to avoid the disapproval of parents and the possibility of punishment from squads of a kind of moral brigade active in Mali in the late 60s and 70s. Yet, in apparent contradiction, the wearers of these outfits were documented by enterprising photographers, and the resulting photographs were displayed for sale in the photographers’ studio the following day. How could an apparently public, permanent medium be so embraced by young people engaged in hidden, fleeting activities? What kinds of meanings did they make from James Brown, from bell-bottom trousers, from dancing popular hand dances? and how were those pop cultural forms transformed by young Malians? Writings by Mamadou Diawara and Tsisti Ella Jaji were helpful in thinking about global black culture, connectivity through consumption, and pan-African imaginaries.

Today these snapshots by the studio of Malick Sidibe (in particular) and other photographers are celebrated, wrapped in nostalgia and imbued with the hopeful spirit of the early independence moment. The clandestine quality of some of the activities they document is not much discussed in connection with the pictures, but it changes them, makes them images of conflict in addition to celebration: the participation in global youth culture is insistent, in opposition to the state’s view of what a modern young African could be. See lots more photos by Malian photographers in the very awesome Archive of Malian Photography led by Candace Keller at Michigan State University.

Recommended listening: Boubacar Traore’s “Kar Kar Madison,” his late-60s version of a hugely popular line dance that was created in 1957 by members of a black dance club in Columbus, Ohio.

Though sponsored by Lusophone Studies Association, my paper was included as a kind of comparative case. I was nervous to be in there with a bunch of historians! Thanks to the panel organizers, to Marissa Moorman for the invitation, and to discussant Richard Roberts for his comments.